- Home

- Biography

- Medal of Honor

- Honors

- Ed Kelley Memorial Plaza

- J. Edward Kelley Society

- Jonah E. Kelley Army Reserve Center

- Jonah E. Kelley Memorial Bridge

- Jonah Edward Kelley Day

- Kelley Barracks, US Army Base

- Kelley National Guard Armory

- Medal of Honor Book

- Medal of Honor Grove

- USAT Sgt. Jonah E. Kelley

- USNS Sgt. Jonah E. Kelley

- 78th Lightning Division Memorial

- Ed’s Journey to WWII

- Galleries

- Family

- Contact

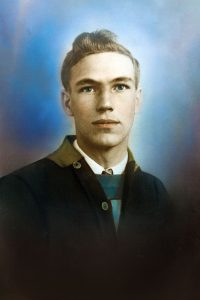

Jonah Edward Kelley

Medal of Honor Recipient

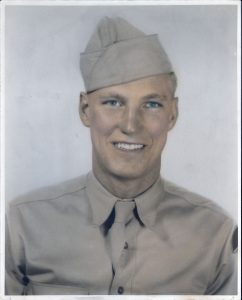

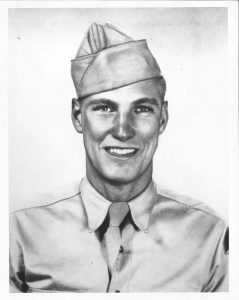

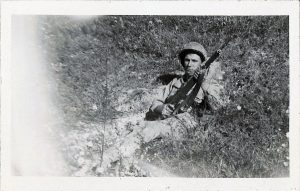

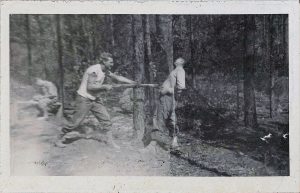

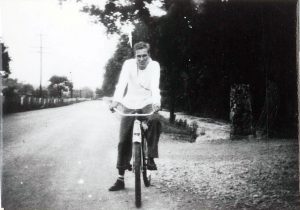

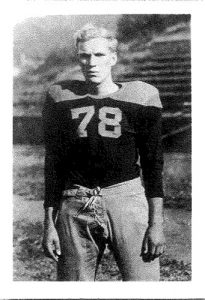

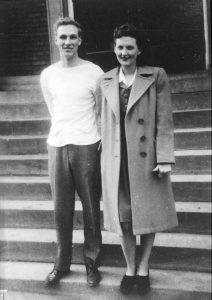

Photos of Jonah Kelley

Ed was a normal boy, growing up with a zest for adventure and knowledge, and along the way he acquired leadership skills. In fact, the reader will surely smile in reading Chapters 3, 4 and 5, which recount the numerous youthful activities of Ed and his friends, in a day when young people had no video games or texting devices to occupy their time but had to come up with games and pastimes using only the resources provided to them by friends and the local environment.

“As his character developed, his classmates came to look on him as a natural leader whose principles of conduct could not be compromised in any situation. At the proper moment, a look or a gesture form Ed could be worth a thousand profanities. His good nature was uncluttered by grudges or recriminations, while trust in his parents’ judgment solidified his own emergeing values.”

“By the time he had reached his teens, Ed’s reputation for honesty had become proverbial, and Lester Gates recalls that if he owed a penny he’d walk a mile to repay it.”

After the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, everyone wanted to join the service. Ed was determined to join the Marines but they turned him down, claiming he was color blind. A year later he was able to take an Army physical which found no such difficulty, and he was soon on his way to training and, eventually, deployment.

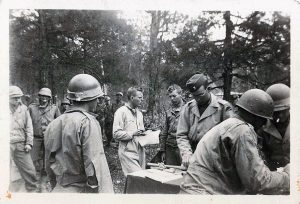

Ed was one of those assigned to the newly reactivated 78th Lightning Division and rose steadily through the ranks until he was a staff sergeant by the time of the battle of Kesternich in Germany, where he won the Medal of Honor and lost his life.

Kesternich itself was a small town in Germany near its border with Belgium, but its location was strategic and it needed to be taken in order for allied troops to advance. An earlier attack had failed to rout the German defenders. This time, it was the Lightning Division’s turn to try.

Kesternich was a much smaller town than Keyser, having only 112 buildings in it. But those buildings had been taken over by German forces and Ed’s outfit had to clean them out, building by building.

On Jan. 30, 1945, Ed had already been wounded — in his back and his left hand. Instead of retreating to a medical station, he put a rough bandage on the shattered hand and used his rifle with only his right hand, “resting it upon rubble or over his left forearm.” When it was necessary to toss hand grenades, he’d put his rifle down and pull the grenade pin with his teeth.

He did all that because of his sense of responsibility for the men under his command. Instead of ordering them forward, he preceded them, rushing one house and killing three enemy soldiers, clearing the way for his squad to advance. He then killed a sniper and another charging enemy soldier. The next morning, he left his squad in a safe location and advanced to kill an enemy gunner dug in under a haystack. Once again finding his squad unable to advance due to a machine gun nest, he ordered them to remain in a safer position and attacked the gun single-handed, being brought to his knees in a hail of fire. Before he died, he shot dead all three of the machine gunners.

The Medal of Honor is sometimes called “The Congressional Medal of Honor” because the President of the United States presents it “in the name of The Congress.” The formal language of Sergeant Kelley ‘s citation doesn’t really tell the story of Ed Kelley.

– George T. McWhorter