- Home

- Biography

- Medal of Honor

- Honors

- Ed Kelley Memorial Plaza

- J. Edward Kelley Society

- Jonah E. Kelley Army Reserve Center

- Jonah E. Kelley Memorial Bridge

- Jonah Edward Kelley Day

- Kelley Barracks, US Army Base

- Kelley National Guard Armory

- Medal of Honor Book

- Medal of Honor Grove

- USAT Sgt. Jonah E. Kelley

- USNS Sgt. Jonah E. Kelley

- 78th Lightning Division Memorial

- Ed’s Journey to WWII

- Galleries

- Family

- Contact

Jonah Edward Kelley

Medal of Honor Recipient

Kelley’s Journey to WWII / Rhineland Campaign

Introduction

After reading, be sure to check out the recent images [link] of Kesternich & where Kelley was killed [link] during the Second Battle for Kesternich.

Ed was a normal boy, growing up with a zest for adventure and knowledge, and along the way he acquired leadership skills. In fact, the reader will surely smile in reading Chapters 3, 4 and 5, which recount the numerous youthful activities of Ed and his friends, in a day when young people had no video games or texting devices to occupy their time but had to come up with games and pastimes using only the resources provided to them by friends and the local environment.

“As his character developed, his classmates came to look on him as a natural leader whose principles of conduct could not be compromised in any situation. At the proper moment, a look or a gesture form Ed could be worth a thousand profanities. His good nature was uncluttered by grudges or recriminations, while trust in his parents’ judgment solidified his own emergeing values.”

“By the time he had reached his teens, Ed’s reputation for honesty had become proverbial, and Lester Gates recalls that if he owed a penny he’d walk a mile to repay it.”

After the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, everyone wanted to join the service. Ed was determined to join the Marines but they turned him down, claiming he was color blind. A year later he was able to take an Army physical which found no such difficulty, and he was soon on his way to training and, eventually, deployment.

Ed was one of those assigned to the newly reactivated 78th Lightning Division and rose steadily through the ranks until he was a staff sergeant by the time of the battle of Kesternich in Germany, where he won the Medal of Honor and lost his life.

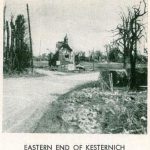

Kesternich itself was a small town in Germany near its border with Belgium, but its location was strategic and it needed to be taken in order for allied troops to advance. An earlier attack had failed to rout the German defenders. This time, it was the Lightning Division’s turn to try.

Kesternich was a much smaller town than Keyser, having only 112 buildings in it. But those buildings had been taken over by German forces and Ed’s outfit had to clean them out, building by building.

On Jan. 30, 1945, Ed had already been wounded — in his back and his left hand. Instead of retreating to a medical station, he put a rough bandage on the shattered hand and used his rifle with only his right hand, “resting it upon rubble or over his left forearm.” When it was necessary to toss hand grenades, he’d put his rifle down and pull the grenade pin with his teeth.

He did all that because of his sense of responsibility for the men under his command. Instead of ordering them forward, he preceded them, rushing one house and killing three enemy soldiers, clearing the way for his squad to advance. He then killed a sniper and another charging enemy soldier. The next morning, he left his squad in a safe location and advanced to kill an enemy gunner dug in under a haystack. Once again finding his squad unable to advance due to a machine gun nest, he ordered them to remain in a safer position and attacked the gun single-handed, being brought to his knees in a hail of fire. Before he died, he shot dead all three of the machine gunners.

The Medal of Honor is sometimes called “The Congressional Medal of Honor” because the President of the United States presents it “in the name of The Congress.” The formal language of Sergeant Kelley ‘s citation doesn’t really tell the story of Ed Kelley.

– George T. McWhorter

Keyser to Kesternich

In June 1941, just six months before the Japanese attacked the American Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor, precipitating America ‘s entry into World War II, Jonah Edward Kelley, a deeply religious student athlete who worked hard and made good grades, graduated from Keyser High School in the mountains of northern West Virginia. He was then eighteen and destined for college. Under his graduation picture in the high school yearbook is his quote, ‘ Today I am a man.” He would not live to see his twenty-second birthday.

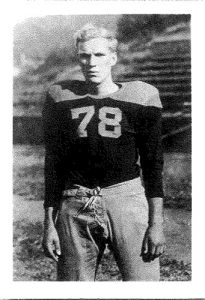

Kelley was in his second year at Potomac State College when he was drafted on March 8, 1943 and was assigned to the 78th Lightning Division which had distinguished itself in World War I at the battles or St Mihiel, Lorraine, and the Meuse-Argonne. Reactivated in World War II, the 78th trained at Camp Butner, North Carolina, where Kelley, six feet two and 175 pounds, became heavyweight boxing champion of the division. Barely 21, he was soon promoted to staff sergeant and squad leader, 1st Platoon, ‘”E” Company, 2nd Battalion, 311th Infantry Regiment.

When the division was ready for action it was sent to Europe, arriving in England October 26, 1944, made part of VII Corps and was on the Western Front by December 1. Allied armies confronting the Germans in the fall of 1944 had arrived on the European continent through two great invasions, Operation Overlord centered on the beaches of Normandy in June and Operation Dragoon on the southern coast of France in August. September found the Allied armies arrayed in strength on the doorstep of the Third Reich, from Antwerp, Belgium south to the Swiss frontier. Victory seemed within reach.

American General Eisenhower was commander in chief of the Allied Forces. His strategy at that phase of the battle was to attack on a broad front British Field Marshal Montgomery was to cross the Rhine River at Arnhem, Holland. To the south, the Americans were to advance primarily against the industrial Rhur north of Cologne and secondarily, south of Luxembourg and the Ardennes forest toward the Saar.

Although the German Army suffered a million casualties on all fronts in the summer of 1944, millions more remained in uniform In addition, the German defensive West Wall, the Siegfried Line, stretching from the Netherlands to Switzerland was formidable, if not impregnable. In early September Hitler put the defense of the Western Front under the command of Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, directing him to stop the allies at the Siegfried Line long enough for the German Army to regroup for a massive counter offensive. The American Army VII Corps began its attack on the westernmost German City of Aachen on October 2, surrounded it on October 10 and demanded its surrender. Aachen, the birthplace of Charlemagne and a symbol of Nazi ideology, was ordered by Hitler to be held at all costs. The defenders of the city fought house-to-house for eleven days until finally the remnants of the garrison capitulated.

After the fall of Aachen, the Allied plan was to continue the fight throughout the winter, advancing at all points along the line. There was, however, a thorny problem, the Hurtgenwald – the Huertgen Forest. The crossroads town of Schmidt, eighteen miles southeast of Aachen, dominated the Huertgen area and the Roer dams; its capture was the linchpin of the winter operation.

As described in a brochure prepared in the U. S. Army Center of Military History, Rhineland Campaign, by Ted Ballard, The Huertgen Forrest was a dense, primordial! woods of tall fir trees, deep gorges, high ridges, and narrow trails; terrain ideally suited to the defense. The Germans had carefully augmented its natural obstacles with extensive nine fields and carefully prepared positions because they realized something the Allies had not yet fully grasped- losing Schmidt exposed the Roer River dams to attack. So long as the Germans controlled the dams, they could flood the Roer River Valley, thereby destroying Allied tactical bridging and trapping any units that had crossed the river. These isolated forces could then be destroyed by German reserves. Consequently, the Germans were determined to hold Schmidt, knowing the almost impenetrable terrain of the Huertgen Forrest would add depth to their defense and neutralize American superiority in aircraft, tanks and artillery.

The conquest of the town of Schmidt, six miles east of the Belgian-German boundary, was assigned to the 28th Infantry Division, which launched its attack on November 2nd. For eleven days the 28th and three German divisions, one a Panzer unit, slugged it out until finally, after suffering more than 6,000 casualties and losing almost fifty tanks and tank destroyers and vast numbers of trucks, guns and individual weapons, the battered 28th was withdrawn.

From November 13 through December 15 the Americans committed the 8th , 9th and 47th Infantry Division, 2nd Ranger Battalion and 46th Armored Infantry, Battalion into the hell of Huertgen and sustained 21,500 additional casualties~ but with little gain to show for its losses. On December 13, the newly arrived 78th Lightening Division, Ed Kelley’s division, joined the battle, moving out from Lammersdorf, just across the German frontier, its objective – to seize Schmidt. However, its advance was halted three days later when the Germans began their counter offensive in the Ardennes, the ”Battle of the Bulge”.

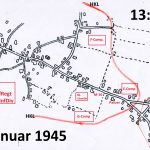

Since late Novvember (1944) the Roer River had constituted a barrier lo the Allied armies on the Western front. The huge Schwammenauel Dam near Schmidt was a potent flood threat lo any supply lines of Allied forces attempting to operate east of the Roer. This threat had to be removed; Schmidt had to be taken. Schmidt sat scarcely astride the ground and approaches to the dams. Earlier in the fall it had been occupied by elements of an American division, only to be forcibly and permanently ejected. Another American division had attempted lo lake Schmidt but was slopped cold in Bergstein, three miles to the north, but twice that far by tortuous road. On 13 December 1944, the 78th “Lightening” Division launched an attack from the vicinity of Lammersdorf, eight miles east of the dam, pushed southeast three miles through Rollesbroich, Simmerath, and into Kesternich against steadily increasing enemy resistance. There on the 16th and 17th of December 1944, the Germans counter attacked. They recaptured Kesternich, lost it and again retook it, this time to hold it. Elements of three American infantry Battalions with supporting tanks and tank destroyers had been in Kesternich. The Germans had taken a heavy toll of Americans, including a battalion commanding officer, a battalion executive officer and virtually all the members of four rifle companies.

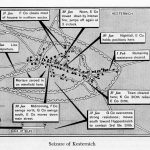

Kesternich had a triple strategic value. First, it was situated on high open ground, with excellent observation directly into the enemy’s main defenses at Steckenborn and Strauch, two kilometers to the north. Second, Kesternich controlled the approaches to Ruhrberg, four kilometers to the east on the western bank of the Roer River and troops in Ruhrberg were in position to attack Woffebach to the north, and out-flank the Steckenborn-Strauch defenses. Third, and most important to the Germans, Kesternich provided observation of the important road from Simmerath on the west to Schmidt on the north, and the assembly areas for a German counterattack against allied effort toward Schmidt. Kesternich had to be controlled before the main effort against the Schwammenauel Dam could be launched.

On January 30, 1945, the terrain was heavily blanketed with snow, nearly knee deep in the open fields and, with drifts over a man’s head in some places. A sunken road in Kesternich had drifted level full. This heavy snow impeded rapid movement and furnished the enemy with a good background against which un-camouflaged figures were readily visible. Snow did aid the attackers in that the heavy anti-personnel mine fields of the Germans were rendered partially impotent, and artillery and mortar bursts were somewhat smothered. This, themeselves the situation before dawn at 0530 on January 30, 1945, when the 2nd Battalion, 311th infantry … jumped off in the attack on Kesternich. Each man carried a one pound block

of dynamite, and each machine gun crew-member carried a twenty pound shape charge. The explosives were to be used to soften the frozen ground the aid in digging in. Improvised snowsuits had been made from bed sheets. Snow, driven by a light northeast wind, was falling steadily as the attack jumped off on time. It was still dark and there was some confession as the men floundered through the snow and drifts, over the fences, and through the hedgerows.

By 0600 it was getting light, and contact had been made with the enemy’s main defenses. The men set about breaching the wire and anti-personnel mine fields. The enemy opened up with their protective line fires: 50 and 120 mm mortars and 105 mm artillery. Panzerfausts (one time, disposable, anti-tank rockets) were fired at trees to get bursting effect on the troops, an SP 75 (self-propelled 75 mm cannon) opened up on the tanks machine guns and automatic weapons began to fire. (Later reconnaissance revealed that approximately 50 percent of the enemy weapons were automatic.) The attack bogged down and the (Americans) tanks were called forward. Within five minutes their radio communication was out. Again, the attack stopped.

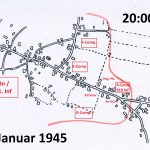

For the remainder of the day the troops slogged forward, fell back, and regrouped, moving house to house further into Kesternich, encountering mortar and artillery, small and machine gun fire. In the cold, the automatic weapons began to freeze. Several tanks were knocked out and fifty-five casualties were sustained. Some German soldiers were captured and questioned and questioned. They advised that their orders were to hold Kesternich at all costs.

During the night, the disabled American tanks were removed, the wounded evacuated and the units consolidated and reorganized. Enemy mortar and artillery bombardment continued through the dark hours. After darkness fell, the Germans brought up reinforcements and laid new anti-personnel and anti-tank mines. Although it had slopped snowing, it was windy and bitterly cold. Very few of the men had any camouflage clothing left.

At 0830 the next morning, after a five-minute artillery barrage, the American attack began again. There had been a two hour delay on the replacement platoon and company commanders could comprehend their attack orders and “get a feel” for the terrain. The 1st platoon of E company, Ed Kelley’s platoon, was to attack on the east side of the main street and secure that part of the town, house by house. The sun emerged about noon and the snow began melt. By 1400 the ground was slippery although there was still a six-inch blanket of snow over everything. Continuing with Battalion Commander Keyes’ description:

“E” COMPANY HAD THE ROUGHEST FIGHT OF THE DAY… the enemy had organized positions about 150 yards from our front lines, furthermore, they did not withdraw from a single building they held. The first platoon (Kelley’s) had to drive them from building 90 And the other buildings in its vicinity before they came against the main enemy positions. Three tanks supported the Americans with machine gun and cannon fire, as they slowly advanced through the prepared gaps in the minefields on the south. Though the coordinated action of the 1st and 3rd platoons and the tanks, the enemy position was penetrated. The attack now became a slugging match.

The enemy occupied reinforced sandbagged positions inside buildings, firing through embrasures that were formed by knocking out a foundation block. In at least two instances machine guns were fired in one building by personnel manipulating a wire from another building. ‘l’he advance was slow and tedious and was accon1plished by having a tank fire at a building, breaching the wall, and permitting the men to enter and mop up. This continued all the way through Kesternich so that, at the end of the day, every building had been smashed and most of them burned. Sgt. Jonah E. Kelley, squad leader of the 1st platoon, led his squad from building to building. He would establish a base of fire and under its cover, was the first to enter each building. Then he covered the advance of his squad and together, they 1nopped up. In one instance when his squad was held up by a machine gun, which a tank and hand grenades had failed to dislodge, Sergeant Kelley burst into the open, was hit by a German bullet and knocked down, but he killed four and wounded another before he died. His action in knocking out the German machine gun permitted hi s squad to advance.

“E” Company lost all its platoon leaders and platoon Sergeants, plus a good many squad leaders. The Company had received forty-three additional casualties and an unknown number of dead. There were only eight of the fifteen tanks left.

That night the temperature dropped. Water froze in canteens ad foxholes. First stages of trench foot, a disabling disease of the feet caused by exposure to cold and wet, began to appear. The men who had survived the battle were numb with cold and suffered from exposure. When the canteens froze solid they were forced to eat snow to get water. Fingers were so stiff that casualties were unable to unwrap their wound tablets. Frostbite was prevalent and in some cases gloves froze to the men’s hands. One hundred eighty-four enlisted men and six officers had been killed, wounded or were evacuated due to exposure, but Kesternich had fallen. The town of Schmidt was captured on February 8, and the Schwammenauel Dam the next day. A month later, on March 8, 1945, a unit of Kelley’s 78th Division was the first infantry to cross the Rhine River on the Ludendorf railroad bridge at Remagen, the sole remaining functional bridge over the Rhine. The Germans had tried but failed to destroy it.

Post War

On April 10, 2002, speaking at the fifty-seventh annual Keyser High School “J. Edward Kelley Award Assembly,” Maj or General David C. Meade, U. S. Army, retired, suggested that the heroic actions of Sergeant Kelley on January 31, 1945 probably shortened the war in Europe by two months and may have altered the course of history. If the war had dragged on in the west and if the allied forces had not met the Russian army at the Elbe River, Austria and Denmark might well have been occupied and dominated by the Soviets.

How that realignment would have affected the outcome of the Cold War is anybody’s guess, but that altered political arrangement would surely have had a negative impact on the free world. Today, there is a new high school in Keyser, West Virginia. The old one, from which Ed Kelley graduated in 1941 has become a business center, home to forty or so shops and offices. In the new high school, appropriately identified and prominently displayed in a glass case just inside the main entrance, is Staff Sergeant Kelley’s Medal of Honor. His younger sister, Georgianna, gave it to the school in 1999, one year before she died. Ed Kelley is remembered in Keyser – not as a soldier – but as a smiling, tall and good-looking high school kid who loved sports, his church, his life, his town and the people there.

He is home again. His modestly marked grave, next to the graves of his parents and his sister, is on a hillside, overlooking the picturesque, rolling hills of West Virginia. And, in Stuttgart Moringen, Germany, about 250 miles south east of the village where Ed Kelley was killed in action, still stands Kelley Barracks, one of the remaining outposts of the American Army in Germany. For almost fifty years it has been an important American Army Corps headquarters, essential in our struggle against the Soviets to win the Cold War.

The account of Sergeant Jonah Edward Kelley’s activities leading to his death in combat was taken from An After-Action Report for the Second Battalion, 311th Infantry Regiment, 78th (“Lightning”) Division for the period 30 January 1945 to 7 February 1945, written by Lt. Col. Richard W. Keyes, Commander of that Battalion, entitled From Kesternich To Schmidt and published in Volume MMII, Number 2, of The Flash, a publication of the 78th Infantry Division Veterans Association, dated April, 2002.

Monographs – The Attack on Kesternich, Germany 30 January – 1 February 1945

To better understand the war, officers were asked to write monographs on their personal experiences at work. With these works, future wars can be better understood. Here is the personal experience of a Company Commander, Captain John H. Barner, Infantry.

Download here: Battle of Kesternich – Mongraph by Barner, John H. CPT.pdf